[ad_1]

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

The yield curve is indicating a US recession could begin as early as June. The likely rapidity of its onset means the Fed will have to loosen policy sooner and by more than the market is currently pricing.

Recessions have gone out of fashion, with fears one will hit in the next year down sharply, according to BofA’s Global Fund Manager Survey. But the sugar high of some recent, rosy economic prints is not yet enough to derail the weight of evidence pointing the other way.

It’s true the nature and timing of the next recession may be different this time due to the extraordinary circumstances of the pandemic. The change in sequencing already looks unusual: normally inflation only starts falling once the recession has begun, and real wages do not get a boost until almost a year after the recession’s onset.

Recessions are caused when a number of different cycles – the income cycle, the inventory cycle, the credit cycle, the employment cycle – begin to worsen at the same time, and reinforce one other.

Currently real incomes and housing are enjoying reprieves from slowing inflation and an easing in the pace of rate hikes, although these will be fleeting as prices soon begin to rise again, and high absolute rates continue to plague housing.

Those reprieves are just painkillers, masking the discomfort but not treating the underlying causes. Credit continues to tighten, manufacturing remains depressed, and consumer and business expectations on the economic outlook continue to be fairly dire. The change of sequencing only delays – and does not avert – the recession.

But the clock is now ticking, and the yield curve is signaling the next recession could begin as early as the middle of this year.

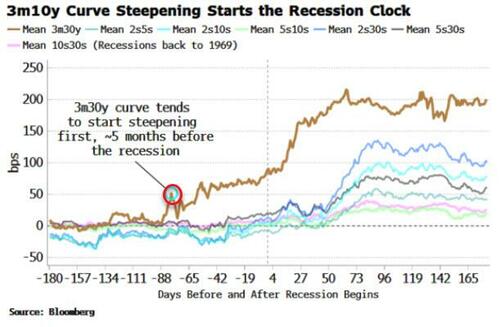

While the yield curve’s inversion tells you a recession is on the way, it’s the subsequent re-steepening that indicates the slump’s imminence. Not all yield curves are alike, and some parts of it begin to steepen much sooner than others. One of the first to move is the 3m30y curve. In previous recessions it started to steepen well before most other parts of the curve.

The 3m30y curve has been steepening since mid January, the longest it has risen without making a new low since it peaked last May. This is significant as the curve has not re-flattened despite the Fed recently galvanizing its hawkishness.

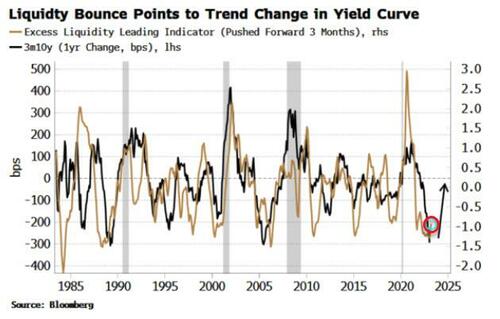

Knowing if and when a trend has fundamentally changed before the fact is by definition tricky, but the steepening comes at the same time as a rise in excess liquidity (the difference between real money growth and economic growth).

Excess liquidity is one of the few indicators that gives a lead on the yield curve, itself a leading indicator. Today’s yield-curve steepening becomes very noteworthy when combined with the turn in excess liquidity, and gives credence to the notion that the 3m30y curve has indeed bottomed.

Most of the “no-landing” optimism comes from robust employment data. But there are enough doubts here to permit some healthy skepticism. Payrolls have added significantly more jobs than the household survey since last March, as more jobs have been created than employees. Payrolls are thus likely overstating underlying economic resilience if a rising number of people need more than one job.

Further, the birth-death adjustment has added 1.3 million jobs to non-seasonally-adjusted payrolls, mainly driven by the Quarterly Consensus on Employment and Wages (QCEW). But this has started to revise payrolls down, recently taking them 287k lower in 2Q22.

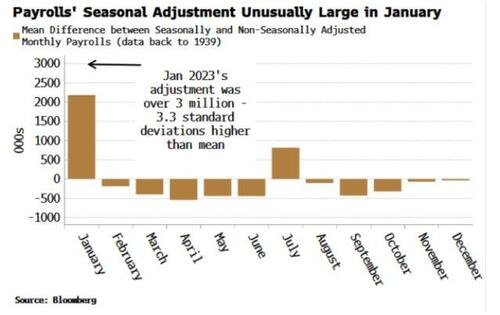

Also, the +517k monster payrolls print that fueled most of the recent optimism was affected by a much larger than normal seasonal adjustment, even for a January. Without the adjustment, over 2.5 million jobs were lost last month.

Employment data is among the most lagging and heavily revised. It is one of the reasons recessions appear to happen so fast as it becomes clear the economy was already faring worse than thought.

But the Fed will focus on the data as it is. When you combine this with the current disinflationary trend in the US likely on the cusp of ending due to a China-driven global cyclical upturn, the central bank is poised to keep policy tighter for longer.

The downturn is thus liable to be worse, leaving the Fed needing to cut rates more. The maximum inversion in the yield curve this cycle would be historically consistent with over 500 bps of rate cuts.

This is not a prediction, but it suggests that the Fed will cut more than is currently priced. As long as it is in higher-for-longer mode, more cuts should be priced.

Specifically, red Eurodollar/SOFR futures (2024 expiries) should start to rally, and spreads such as March 2024 versus March 2025 have potentially much further to fall.

Loading…

[ad_2]